Darwin’s voyage on the Beagle was a key turning point in his life, as he acknowledges in his Autobiography:

’The yoyage of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life, and has determined my whole career’.

Such is the importance of the Beagle voyage in the history of science it is remarkable now to look back at how it came about, and how very close it came to not happening!

Getting On Board

Darwin had been ‘geologising’ in Wales with one of his Cambridge mentors Adam Sedgwick in the summer of 1831. He came home to a letter from his great friend John Henslow. The letter contained exciting news; Capt. Robert FitzRoy was seeking a young naturalist to accompany him on a two year voyage to survey the coast of South America. Darwin was full of stories of the great Victorian travelling Naturalists, such as Alexander Von Humbolt, and was immediately keen to accept. Unfortunately for him his father, fearful that the voyage would be a distracting waste of time, squashed his dreams, unless that is he could ‘…find any man of common-sense who advises you to go’.

Deflated, Charles wrote declining the offer and went to the Wedgewood’s estate to take out his disappointment on the local birds. But he carried with him a letter from his father to Uncle Jos asking what he made of the Beagle offer. Jos was much more in favour of the trip, thinking it an ideal opportunity for a man of ‘enlarged curiosity’ such as Charles. Together they rushed back to Shrewsbury and persuaded Dr. Darwin of the trip's merits, who promised ‘all the assistance in my powers’. The trip was on.

It turned out though that the offer had been misconstrued to Charles. The position had in fact been turned down by two of Darwin’s Cambridge crowd and at this stage Darwin was still second choice to a friend of Capt. FitzRoy. On hearing he was still just a back up, Charles was again crushed and had ‘entirely given it up’.

But his luck carried; FitzRoy called Darwin to visit him in London, his friend had refused. Despite FitzRoy’s fears that Charles’s nose signified a lack of energy and determination, Charles was offered the place. Darwin was back on the Beagle.

The Beagle & Its Crew

The British Admiralty had begun surveying the South American coast in the 1820s: it was of great importance to the empire which was competing with Spain and the United States for the bounty of natural resources. The Beagle’s brief was to continue the task of mapping coastlines and sounding out harbours and channels.

Darwin’s role was to be a private naturalist. He would have to pay his own way (or rather his father would) but would dine and socialise with the captain. FitzRoy had sought such a companion as he feared the isolation of command at sea would be costly. The Beagle’s previous captain had shot himself while surveying in South America, FitzRoy’s family had a history of depression and his uncle has slit his own throat (a path FitzRoy himself would follow many years later).

FitzRoy actually landed the job in as haphazard a way as Darwin gained his own place aboard. On a previous trip to Tierra del Fuego FitzRoy had captured some Fuegians. As an evangelical experiment he decided to bring them to England to teach them ‘English... the plainer truths of Christianity… and the use of common tools’ (they were named Fuegia Basket, York Minster and Jemmy Button). This done he sought to take them back as missionaries, but unable to find a ship to do so he was on the verge of setting sail at his own cost when his uncle persuaded the Admiralty to give him captaincy of the Beagle.

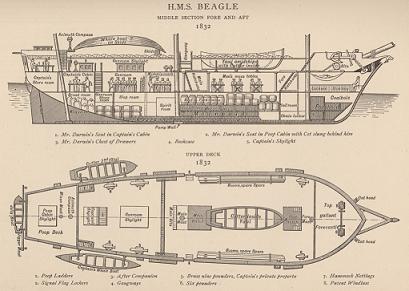

The Beagle itself was a small vessel, only 90 feet long and 24 feet wide. She was being refitted for the journey when Darwin first set foot on board. He was stunned by how small it was, with only two cabins; the larger was to be Charles’ lodgings – the poop cabin. It was 10 feet by 11 feet and home to a large chart table, he would have rights to a wall of drawers and the ship’s library. He was to share it with the assistant surveyor John Lort Stokes (19) and possibly with the young Midshipman, Philip King (14). Charles would sleep in a hammock rigged up over the chart table. A cramped place to call home for what would turn out to be 5 years. Read on...

Written by Stephen Montgomery

References & Further Reading

The Autobiography of Charles Darwin

by Charles Darwin (Edited by Francis Darwin), The Thinker's Library: 1929

Charles Darwin

by Cyril Aydon, Robinson: 2003

Darwin

by John van Wyhe, Andre Deutsch: 2009

Darwin

by Adrian Desmond & James Moore, Penguin: 1991

Darwin: Discovering the Tree of Life

by Niles Eldredge, WW Norton & Co.: 2005

Evolution's Captain

by Peter Nichols, Profile Books LTD: 2003

Journal of Researches

by Charles Darwin, 1839 (any edition)

The Life of Charles Darwin

by Francis Darwin, Senate: 1995 (1902)