Darwin’s great book is titled On the Origin of Species, but some have said this is misleading. Darwin discusses evolution, common descent and natural selection at great length and with much supporting evidence, but what does he say about how new species arise? And what do we know now about the origin of new species?

The Species Problem

Anybody discussing the evolution of a species has first to broach one particularly tricky problem: what is a species? Biologists have grappled with this problem both before and after Darwin’s time, and Darwin himself acknowledges this: ‘no one definition (of species) has as yet satisfied all naturalists; yet every naturalist knows vaguely what he means when he speaks of a species’.

Nowadays we generally recognise four ways of thinking about a species:

- a typological species differs from other species by a constant set of characters; this view stems from creationist views of the origin of species

- a nominalist species concept claims there are only individuals! The name given to a species is just an arbitrary name given to a bunch of individuals

- the evolutionary species was defined by the palaeontologist G.G. Simpson as a ‘lineage evolving separately from others and with its own unitary evolutionary role and tendencies’

- the biological species concept was defined by Mayr: ‘species are groups of interbreeding natural populations that are reproductively isolated from other such groups’

There is still debate over which definition is best, and all have uses in different fields. However it is generally agreed that there must be real distinctions among the groups of organisms that are classed as species. There is, however, no clear agreement about how Darwin himself viewed species. In one of his early notebooks he writes ‘my definition of species has nothing to do with hybridity, is simply an instinctive impulse to keep separate’ indicating that he was thinking about reproductive isolation and species in a similar way to thebiological species concept. By the time he wrote The Originhowever, whilst he still considered isolation as an important factor, there is some indication that he reverted to a mixture of nominalist and typological species concepts, saying genera are merely convenient artificial combinations.

What Is Speciation?

If species aren’t special creations, where do new species come from? Darwin found the answer by concluding that lineages change over time and also multiply – they split in two. For Darwin, and all who followed, speciation is this process of multiplication, occurring when one population splits into two reproductively isolated populations.

Of major importance to Darwin’s thinking about speciation were the mockingbirds and finches of the Galapagos Island which Darwin correctly believed had each descended from one Central American species and multiplied on the islands. New species were created as populations became adapted to filling different roles on the island. This observation led Darwin to conclude that new species form by gradual evolution and isolation from an ancestral population; eventually this leads to two distinct species. If you catch it in the act, half way through this process you observe what are called ‘varieties’, populations of one species which differ, but not enough to justify being labelled as separate species. For Darwin therefore varieties and species were just different degrees of the same thing: ‘there is no fundamental distinction between species and varieties’.

How Do Species Multiply?

Darwin clearly identified two major factors that contribute to speciation. The first of these is the isolation of populations followed by local adaptation by natural selection:

‘…isolation, by checking immigration and consequently competition, will give time for any new variety to be slowly improved; and this may sometimes be of importance in the production of new species.’

He also singled out migration to and isolation on islands as a means of promoting speciation:

‘If we… look at any small isolated area, such as an oceanic island, although the total number of the species inhabiting it, will be found to be small…of these species a very large proportion are endemic… Hence an oceanic island at first sight seems to have been highly favourable for the production of new species.’

The second factor Darwin discusses is the size of a species’ geographical range; he suggests that if a species covers a large range it is likely to encounter a number of different habitats or environments, especially if it is expanding its range. Natural selection will therefore favour local adaptation to these different environments and will hence promote speciation:

‘…the conditions of life are infinitely complex from the large number of already existing species; and if some of these many species become modified and improved, others will have to be improved in a corresponding degree… the course of modification will generally have been rapid on large areas’.

But how do these populations, once they begin to diverge, come to form separate species? Darwin did not answer this question clearly, and some scholars believe Darwin ruled out the possibility that natural selection has a role in separating species other than in their independent evolution, whilst some passages can be interpreted otherwise.

The answer to this problem is credited to Alfred Russel Wallace and is now known as the Wallace Effect. This idea was published in Wallace’s Darwinism in 1889, several years after Darwin had died. The Wallace Effect proposes that natural selection contributes to reproductive isolation by encouraging diverging populations to stop mating. Each population will have adaptations which increase its fitness in a local environment; matings between individuals of the two different populations will jumble up these adapatations with the result that the offspring cannot compete with individuals from either population; so the mixed offspring have decreased fitness. Now if an individual of one population were to breed with one from the other, they will have less successful young than if they mate within their own population. So natural selection acts to favour either behavioural or morphological mechanisms to prevent mixing, over time the two populations become reproductively isolated and form two species.

Did Darwin Get It Right?

Darwin was certainly much less clear about his views of how species multiply than about his other theories such as common descent and natural selection. However the initial insight to see that species must multiply is remarkable in itself and Darwin does discuss the main factors which we now know affect speciation; isolation and local adaptation to different environments across a species’ range. In doing so he laid the foundations for others to build on his initial ideas.

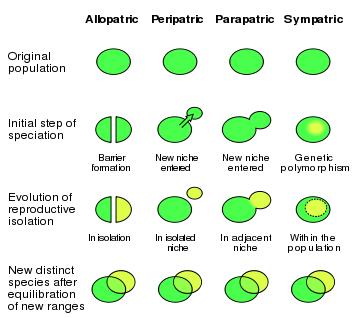

We now recognize four mechanisms of speciation which rely on these two factors:

1) Allopatric speciation – this is the classic island speciation propsoed by Darwin and later extended, most notably by Ernst Mayr. Individuals of a species migrate to an island and become isolated from their parent population; natural selection then acts to modify the founder population.

2) Peripatric speciation – this is much like allopatric speciation but in this case the ‘island’ doesn’t have to be an oceanic island; it could be a isolated mountain top or forest for example.

3) Parapatric speciation – this is akin to the sort of thing Darwin imagined happened if a species expands its range and enters a new habitat or niche. Natural selection will favour local adaptation to meet the demands of this new environment.

4) Sympatric speciation – this is perhaps what Darwin meant when discussing local adaptation to different environments within a species’ range. If new variants arise which are better suited to a particular niche they will be favoured by natural selection.

In each case, if the two diverging populations come into contact again, if they are not already reproductively isolated by chance or by their particular adaptations (for example if one has become nocturnal and the other is diurnal) then the Wallace Effect may lead to their eventual separation.

Examples exist for all four mechanisms; a good example in which all four mechanisms may have had a role is the speciation of Darwin’s finches.

Written by Stephen Montgomery

References & Further Reading

Almost Like a Whale

by Steve Jones, Doubleday: 1999

Darwin: Discovering the Tree of Life

by Niles Eldredge, WW Norton & Co.: 2005

On the Origin of Species

by Charles Darwin, 1859 (any reprint - 2nd edition preferable)

Evolution

by Carl Zimmer, Arrow: 2003

Evolution

by Mark Ridley, Wiley Blackwell: 2003

Evolution

by Nick Barton, Derek Briggs & Jonathan Eisen, Cold Spring Harbour: 2007

Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why it Matters

by Donald Prothero, Columbia University Press: 2007

How and Why Species Multiply

by Peter & Rosemary Grant, Princeton: 2008

One Long Argument

by Ernst Mayr, Allen Lane: 1991

What Evolution Is

by Ernst Mayr, Phoenix: 2002

Why Evolution is True

by Jerry Coyne, OUP: 2009