Upon his arrival back in Shrewsbury Darwin’s friends and family saw a changed man. A great ambition had replaced his old desires, as seen when he declined to go shooting with the Owens, which would never have happened five years previously. Darwin had a lot of work to do, and set about getting it done with renewed energy. By the end of August he was in London to unload his specimens, was introduced to Richard Owen the anatomist at the Royal College of Surgeons, and was elected a member of the Geological Society.

Getting To Work

After sorting some business he realised he would have to live near London so lodged with Henslow before deciding to avoid distraction by renting a house of his own in Cambridge. In January 1837 he began presenting to the Zoological and Geological Societies, went to many dinners with eminent members of the scientific community and met many influential characters, such as Charles Babbage (inventor of the calculator).

He became too busy to travel between Cambridge and London so moved to a property near his brother and spent 7 months preparing his journal for publication. The zoological specimens also needed to be published, as a multi-volume work with coloured plates, but this would be expensive, so Henslow made a personal request to his old friend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, for funding.

Meanwhile, the Zoological Society’s bird expert was taking great interest in the notes on finches and identified them as 14 distinct species, and Richard Owen the anatomist examined the fossils that had been collected, identifying a Giant sloth and what he at first believed to be a Giant extinct llama, both species new to science but related to existing species from South America. This confused Darwin as he was expecting them to be related to animals from similar latitudes in Africa, but instead this information undermined the Creation theory. Lyell suggested the Law of Succession where Providence replaced old animals with similar ones, but Darwin was not convinced.

In September he had to go back to Shrewsbury to recuperate after the onset of heart palpitations that would trouble him for the rest of his life. As the new secretary of the Geological Society he was increasingly in demand but managed to find time to maintain his interest in new ideas. He visited Jenny the orang-utan at the zoo and having never seen an ape before was amazed, noting that man should be humble upon encountering such a creature and consider himself from animals.

Growing Reputations, Growing Ideas

As his reputation grew so did his social network and as a sign of true social acceptance, he became a member of the Athaeneum gentlemen’s club, a gathering place for men of science and letters. On 28th September 1838 Darwin read Thomas Malthus’ economics book An Essay on the Principle of Population, which stated that the human population grows geometrically, unless somehow checked, and food production only arithmetically, and so poverty is inevitable. He realised that competition for resources had parallels in nature, with animals competing for survival. Darwin, who was hunting for a mechanism to explain how species could gradually change over time, was electrified. Clearly plant and animal populations were generally about the same. Yet they too were producing seeds and eggs that would lead them to reproduce at a geometrical rate. The fact that they did not do so showed that their numbers were kept in check. Therefore only a small minority survived to reproduce. Darwin realized that there must be something special about the few that made it. And it was just those few that would pass on their characteristics that would be passed on to future generations. So slight changes in structure that made a little difference to survival would be passed on and added up over time. These lucky few were, as he called it, ‘naturally selected’ because the process was similar to the way breeders and farmers selected which individuals to breed from.

Better Than A Dog

At 28 years old Darwin began to think about settling down, being one of few friends and family living the single life. His father assured him that any son of his would be financially capable of looking after a family so being a very logical man, he wrote a list of further reasons to and not to marry. Some of the reasons on this list are pretty funny, in the column in favour of marriage he wrote ‘object to be beloved and played with – better than a dog anyhow’ but, Darwin reasoned, wives are a ‘terrible loss of time’ (he wrote that one twice!).

His conclusion was ‘marry-marry-marry-QED’, but who? He decided on his cousin Emma Wedgwood, who was the perfect choice due to her many good qualities and an excellent dowry, but he thought she would refuse him having already refused several other suitors. He travelled to Maer on the off chance she might accept, and to the delight of Charles and both families, she did!

The wedding date was arranged for the 24th January 1839 and Darwin returned to London. Election to the Royal Society clashed with the wedding so the latter was moved back to the 29th. Emma and Charles were married and found themselves to be very compatible and lived very happily, agreeing on most issues with the exception of religion. Emma, whilst not being evangelistic, had a strong faith whilst Darwin was increasingly approaching agnosticism.

His Journal was published in the same set with FitzRoy’s account of the journey, which mostly focused on the movement of peoples, as agreed. However, Darwin’s volume received high praise. In August 1839 Darwin’s was published separately and became a best-selling travel book. On 27th December Emma gave birth to William. Darwin was ecstatic and used observations of the child’s development as a study of young animals. In the early months of 1840 his health deteriorated and in April he went to see his father in his capacity as a doctor as he’d lost so much weight. They were able to stop his vomiting fits but didn’t know what was wrong with him. Upon returning home he became worse than before and had to retire to Maer until the autumn.

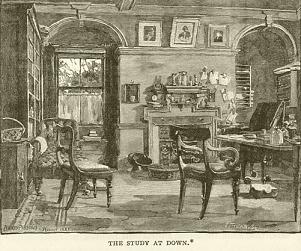

On 2nd March 1841 Anne Elizabeth, Annie was born; in the summer Darwin’s father gave him a loan so that he could buy a larger house for his growing family. He published his work on coral reefs and returned to Maer after the winter to concentrate on his ideas about species. There were different types of dog and horse due to artificial selection by man, so in the wild natural selection led to favourable characteristics changing varieties into species over time. He became convinced that he was correct. However after jotting down a rough first sketch he returned to his full-time occupation of publishing the geological and zoological results of the Beagle voyage. In September he purchased Down House, a former vicarage in Kent which would be his home for the rest of his life.

Sketches

A week after moving to Kent Mary Eleanor was born but died three weeks later, a great blow to the happy lives of the Darwins. Charles focused on his work and a letter from the naturalist George Waterhouse asking about how to classify animals gave him something to concentrate on. He dismissed the suggestion of Linnaeus’ ordering based on physical similarities and instead suggested grouping by genealogical descent. On 25th September 1843 Henrietta, or Etty was born, bringing the household to five.

In January 1844 Darwin spoke to his friend, the botanist Joseph Hooker about ‘transmutation’ as evolution was then known, ideas that were largely considered wrong by most of his fellow respected scientists. In summer he finished his book Geological Observations on the Volcanic Islands Visited by the H.M.S. Beagle and before proceeding with the next book, took some time to expand his sketch of his developing species theory into a 230 page essay. It is often claimed that Darwin asked his wife Emma to publish this after he died. In fact Darwin told her that it was not written for publication and needed considerable work to make it so. If he should happen to die before he had time to do this, he asked her to offer a very large fee of £500 and all of his scientific books and notes to an editor who would need considerable time to work the essay into a publishable condition. Only if this proved impossible was it to be published as is, but with a note explaining it was not written for publication. Darwin listed several colleagues who might be appropriate editors. All of them knew that Darwin believed in some form of evolution.

In October the Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation was published, this book tried to cover the whole history of the universe, saying there was a Law of Development, with an underlying subtext saying authorities and priests had no right to tell people what to believe. It was an anonymous publishing sensation, but was based on a poor understanding of science. Scientists and churchmen lined up to criticise it, fearful that it posed a danger to social order. This brought it home to Darwin that he would need solid evidence and avoid provocative wider issues when his own work came to light. However he never wavered from his own ideas since he was convinced that he had a proper scientific theory with a large and growing collection of evidence, which he would publish after he had finished the numerous projects already begun.

Barnacles Begin

In the summer of 1845 his son George was born. With four children under the age of five the house was very busy and unlike many families of the time the children were included in the daily routine. Other parts of Darwin’s day included the Sandwalk around his garden and being read to by Emma, several other walks and an end of day game of backgammon. He finished the last volume of geology the following summer and returned to his work on species. He realised, however, that to have any weight behind him he needed to gain some qualifications in zoology, otherwise he could be simply dismissed as a gentleman amateur. He found a barnacle he had brought back that was very unusual. He initially intended to just publish a few papers on these barnacles and had nearly done so when in summer 1847 he heard Louis Agassiz, America’s greatest naturalist, speak and say that a complete study of Cirripedes would be a great thing, a challenge Darwin had to take since he was particularly expert in marine invertebrates going all the way back to his days as a student in Edinburgh. Unlike other kinds of living things collected on the voyage, Darwin did not give the marine invertebrates to another scientist to describe. He kept these for himself.

In July 1847 Elizabeth was born, followed in 1848 by Francis. Darwin’s father died in November and he received a £50,000 share of the fortune. He did not have time to make much of this before the onset of winter, when his health severely deteriorated and he became an invalid himself. He travelled to Malvern in Worcestershire for water cure – cold baths, exercise and a strict diet. He couldn’t cope without Emma, so the whole family was moved to be with him for three months, during which he improved greatly. In January 1850 Leonard was born.

Annie Is Lost

In June his eldest daughter Annie became unwell again, a year after three of the children had suffered from scarlet fever. They took her to Ramsgate for a holiday but she became worse over the course of the winter. The doctor who had helped Darwin advised him on how to treat her and she began to improve slowly and was able to celebrate her tenth birthday in March. The following week she contracted flu and was taken to Malvern as soon as she could be moved. Darwin was unable to stay at home so upon word that she had become feverish travelled to be with her. On 23rd April 1851 she died, the greatest devastation of Darwin’s life. He left immediately, leaving Fanny Owen and her husband to attend the funeral on the family’s behalf.

Three weeks later Horace was born but Emma couldn’t distract herself. Her faith was tested, but she believed that one day she would be reunited with Annie. Charles was not so hopeful. By the end of the year he had completed 2 large volumes, one on living barnacles and one on fossils. In September 1854 he had identified 10,000 varieties and his published work received worldwide praise and earned him the Royal Society’s Copley Medal. He returned to work on species and sent letters to experts to fill any gaps he could see in his knowledge. He also kept and bred domestic fowl varieties and begged for the bodies of interesting specimens from friends, boiling them down to study the skeletons.

Written by Sarah Gardner

References & Further Reading

The Autobiography of Charles Darwin

by Charles Darwin (Edited by Francis Darwin), The Thinker's Library: 1929

Charles Darwin

by Cyril Aydon, Robinson: 2003

Darwin

by John van Wyhe, Andre Deutsch: 2009

Darwin

by Adrian Desmond & James Moore, Penguin: 1991

Darwin: Discovering the Tree of Life

by Niles Eldredge, WW Norton & Co.: 2005

The Life of Charles Darwin

by Francis Darwin, Senate: 1995 (1902)