Charles Darwin’s theories of natural and sexual selection apply to humans as they do to any other species. Recent editions of his most famous book, On The Origin of Species, often feature a schematic of human evolution on the cover. In fact, there is little mention of human evolution in this book. Despite writing about the implications of his ideas for the human species very early, Darwin chose not to include the topic in his great masterpiece except to say that ‘light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history’.

Eventually, twelve years after The Origin was published, Darwin did publish his thoughts on human evolution in The Descent of Man in 1871. In this book and his 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Darwin helped lay the foundations for modern biological anthropology, the study of human variation and evolution. But what did Darwin really say about human evolution? Why did he not say it in The Origin? And how has he exerted such an influence over the last 150 years of anthropology?

Close Encounters

Darwin grew up and lived in an age when slavery was still practised in many countries. Even where slavery had been abolished, many still regarded the different ‘races’ of humans as separate creations; white Europeans were considered the most advanced (by white Europeans). Many people though rejected these views, and Darwin was one of them. His family had a history of liberal thinking, and the young Darwin’s views were, at an early age, quite in line with these.

During his aborted medical training at Edinburgh University, Darwin was tutored in taxidermy (stuffing birds and other animals) by a freed black slave called John Edmonston whom Darwin apparently held in high esteem. When Darwin reached South America on the Beagle Voyage, Darwin’s views on the evil nature of slavery and the unity of different human populations as one species were cemented.

These views, though, almost cost him his place on the boat after a fierce row with the ship’s Captain FitzRoy over the treatment of slaves on an estate the party had visited in Brazil. FitzRoy’s temper exploded during the argument and Darwin effectively left the ship! Luckily the captain backed down and apologised.

The Beagle carried with them three native Fuegians who FitzRoy had previously kidnapped and taken to England to ‘civilise’. Part of the ship’s mission was to take these Fuegians home, and for them then to act as missionaries. Darwin met his first native Fuegians in Tierra del Fuego and was greatly intrigued by their culture, which was completely different from western European culture. But looking at FitzRoy’s ‘civilized natives’ – these differences could clearly be overcome… so what was the real difference? Not much! Encounters with native people across South America, Polynesia and Australia confirmed to Darwin that humans were one species.

On his return to England, Darwin lived in London for a while and often visited London Zoo to discuss the specimens he collected with experts. In March 1838 Darwin saw his first ape, an Orang-utan called Jenny. Jenny had a big impact on Darwin, who wrote in one of his notebooks:

‘Let man visit Ouranoutang in domestication, hear its expressive whine, see its intelligence when spoken to; as if it understands every word said - see its affection. - to those it knew. - see its passion & rage, sulkiness, & very actions of despair; ... and then let him boast of his proud pre-eminence ... Man in his arrogance thinks himself a great work, worthy the interposition of a deity. More humble and I believe true to consider him created from animals.’

He wasn’t the only one to see how human-like the Orang-utans at London Zoo were: Queen Victoria described them as ‘disagreeably human’!

Light Will Be Thrown

Darwin was clearly thinking about human evolution before The Origin was published. Famously though, the only mention the topic got in the book was: ‘light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history’. This is perhaps biology’s greatest understatement and most tantalising cliff hanger.

Clearly people reading his book could put two and two together and saw that Darwin’s ideas had massive implications for how humans view themselves. So why did he not spell it out? Or discuss the evidence for man’s evolution?

Undoubtedly there were multiple reasons for Darwin’s omission. One important one may have been that Darwin was writing in a time of great social and political upheaval; parliament was being reformed, and the treatment of the poor and the growing divide between the classes were causing a lot of anxiety. Darwin perhaps wanted to avoid writing on such a contentious issue as human evolution; even without its inclusion he felt his book would be greeted as intellectual heresy; it was controversial enough as it was!

He had of course, provided a great amount of evidence for the action of evolution in a wide range of plants and animals. He had discussed the problems with his theory and provided counter arguments against them. Darwin therefore didn’t need to spell out the implications for humans, nor was it the point of the book. By showing that evolution is generally expected and true across different classes of life those with a particular interest in man’s place in nature could see the answer for themselves.

The Descent

Given Darwin’s reluctance to discuss human evolution in The Origin why did he then decide to publish an account of the topic in 1871? By this time several other scientists, including Thomas Huxley and Ernst Haekel, had expanded Darwin’s theories to the human species. In the meantime Darwin had published on fertilisation of orchids, climbing plants and variation in domestic species. All the while, of course, being limited to a few hours work a day due to ill health; if he had been well The Descent would probably have come out sooner.

But why write it at all? Darwin writes in the introduction to The Descent that writing the book was ‘all the more desirable as I had never applied these views to a species taken so singularly’. But others argue that perhaps Darwin felt previous accounts were not up to scratch. In particular, a major topic of debate still was whether humans were one or more species, a topic Darwin had long had strong views on.

Britain was more settled politically and socially by the late 1860s so, in The Descent, Darwin could finally set his cards out on the issue of human evolution and the races without fear of political reprisals. A major theme in the book then is detailing evidence to support the (correct) conclusion that all humans are a single species, descended from the same ape-like ancestor. Darwin drew his evidence from three main categories; similarities between humans and other primates, similarities in embryological development, and vestigial organs (part of the animal which still develop to some degree but seemingly have no purpose). With this three pronged attack Darwin provided very strong evidence for man’s common ancestry with the living apes, and that all human populations were more closely related to each other than to any living primate; they were the same species.

Darwin’s explanation for the differences between the races was his theory of sexual selection. The book’s full title gives away the plot; The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. The book is actually two in one. In the first half Darwin deals with the similarities and differences between humans, apes and other primates and then again between human populations. In the second half Darwin outlines his theory of sexual selection, by which adaptation to increase the chance of mating successfully can act independently or even against adaptation to increase survival (natural selection). Darwin illustrates this new theory with many examples from the animal kingdom, but he also uses it to explain racial differences. The reason native people from different continents look different is due to differences in mating preferences.

One major omission from The Descent is a discussion on human fossils. By this time fossils of Homo neanderthalensis had been found in Germany but there was no mention of them. Why leave these out? Surely they are pretty good evidence for human descent from another species?

Despite considering himself a geologist, Darwin was very sceptical that the fossil record would provide conclusive evidence to support his theory. The incompleteness of the fossil record as he saw it received two whole chapters of discussion in The Origin. In addition, in the 1860s a great hunt was underway for ancient human remains, mostly being paid for by rich individuals who would offer big rewards for new finds. As such, counterfeit fossils and tools were common and there are a number of well known hoaxes which fooled some quite qualified scientists. Finally, Thomas Huxley, who was a trained comparative anatomist, had dismissed the Neanderthal finds as just a wild, modern human.

Given Darwin’s lack of faith in the fossil record, the common problem of hoaxes and Huxley’s conclusions, Darwin could skate past the issue of fossil human remains without limiting his evidence. By relying on comparisons with apes he could successfully demonstrate shared ancestry. He had no need to risk basing his argument on a few, as yet unverified, remains.

One of the most amazing of Darwin’s predictions in The Descent is his prediction that humans evolved in Africa:

‘In each great region of the world the living mammals are closely related to the extinct species of the same region. It is therefore probably that Africa was formerly inhabited by extinct apes closely allied to the gorilla and chimpanzee; and as these two species are now man’s nearest allies, it is somewhat more probable that our early progenitors lived on the African continent than elsewhere.’

At that time there was no evidence to support this claim, yet by simple observation of the range and distribution of man’s closest relatives and application of his theories, Darwin correctly predicted what we now know is widely supported.

The Emotions

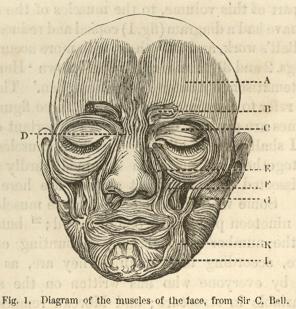

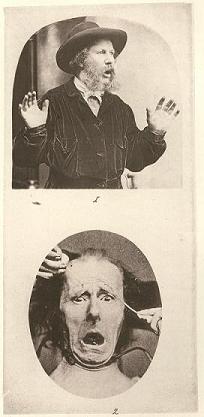

Darwin’s second largely anthropological book was The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. The original motivation behind writing this book was the belief amongst some scientists that the muscles which humans use to convey emotions through facial movements had no counterparts in any other animal; they were unique to man.

This of course does not fit with a Darwinian view of gradual evolution. In The Expression Darwin reports on studies of comparisons between primates and humans, both on their facial expressions and on their facial muscles. He concluded that for both the differences and similarities between man, his primate cousins, and other animals could be easily explained by gradual evolution:

‘it seemed probable that the habit of expressing our feelings by certain movements, though now rendered innate, had been in some manner gradually acquired.’

The differences between human populations could, again, be explained best by their shared ancestry with a ‘single parent-stock’. With this book, and his insistence that each expression demanded a rational explanation, Darwin kick started a field which is now huge: evolutionary psychology. He had started this revolution back when The Origin was published:

‘In the distant future I see open fields for more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation.’

The Stand Off

Darwin’s insistence on treating the human condition, with its civilised societies and conscious mind, as a product of natural and sexual selection was one of the differences in opinion between him and his colleague Alfred Russel Wallace. Wallace did not agree that sexual selection was a major evolutionary force, but argued natural selection was a sufficient explanation, nor did Wallace agree that the human mind could be explained by natural selection

By the late 1860s Wallace had become a Spiritualist, and perhaps linked to this, began to reject evolutionary explanations of human intelligence and abilities, instead invoking “the unseen universe of Spirit”. This, he claimed, had intervened in the normal run of natural selection three times; at the creation of life, the introduction of consciousness, and the generation of man’s mental capacities. Later in his life Wallace also believed in teleology - the idea that the development of the universe has had a direction, and that direction is towards the perfection of man. There are suggestions that Wallace also applied his teleology to evolution. Darwin was clearly a bit perplexed by his former ally’s new views and at one point wrote to Wallace pleading with him not to kill ‘our baby’.

In both cases, Darwin has been proved correct. Modern studies have shown that sexual selection is of massive importance in evolution, and that the human mind can be treated as a product, or by-product, of selection just as any other trait can.

The Legacy

Darwin is mostly remembered for his general theories. But specific fields which he touched, geology, botany and zoology, were greatly changed by his work. Anthropology is the same, as Ian Tattersall, of the American Museum of Natural History in New York and who also did his undergraduate degree at Christ’s College, recently wrote:

‘Virtually every section in the first part of The Descent of Man foreshadows an area of anthropology or biology that has independently flowered since; and in this way, Darwin wrote much of the agenda that was to be followed by paleoanthropology and primatology over the next century and a half’

Written by Stephen Montgomery

References & Further Reading

Becoming Human ~ a great site explaining human evolution through activities and film clips.

The Autobiography of Charles Darwin

by Charles Darwin (Edited by Francis Darwin), The Thinker's Library: 1929

Darwin

by John van Wyhe, Andre Deutsch: 2009

Darwin

by Adrian Desmond & James Moore, Penguin: 1991

Darwin's Sacred Cause

by Adrian Desmond & James Moore, Allen Lane: 2009

The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals

by Charles Darwin, 1872 (any edition)

Journal of Researches

by Charles Darwin, 1839 (any edition)

Principles of Human Evolution

by Roger Lewin & Robert Foley, Wiley Blackwell: 2003

On the Origin of Species

by Charles Darwin, 1859 (any reprint - 2nd edition preferable)

The Descent of Man

by Charles Darwin, 1871 (any edition)

The Human Story: Where We Come from and How we Evolved

by Charles Lockwood, Natural History Museum: 2007