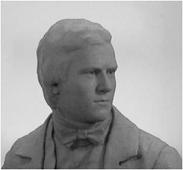

The most common image of Darwin is as an old man with a bushy beard, a bald head, and usually a bit of sour expression on his face. This is a great shame as such images fail to get across the enthusiasm and energy Darwin had as a young man. It was these qualities that helped him make the most of his opportunities about the Beagle.

As Darwin got older he suffered from terrible illnesses; he was constantly sick, often violently so. His illness reportedly caused him to have pretty bad flatulence and his beard was grown to help cover another side effect: boils and acne.

But what was the young man like? What did he look like just before he embarked on a voyage around the world that would change his life? A new sculpture by Anthony Smith can now give us a sense of what Darwin was like as a student.

Missing Images

There are few images of Darwin in his youth; there is one of him as a child about seven years old holding a bunch of flowers beside his sister Catherine. The next we see of him is in a sketch done when he was 31. So we have no record of him as a young adult. To rectify this, and to reconstruct Darwin as the youthful and exuberant student he was Christ’s College commissioned a new sculpture to be made. The sculptor is also a former student at Christ’s.

The Artist

Anthony Smith first read Darwin’s On the Origin of Species aged 16 and was inspired to follow Darwin’s footsteps and to study at Christ’s. He studied Natural Sciences, choosing his courses to specialise in evolutionary theory. He’s now a Fellow of the Linnean Society of London where Darwin and Wallace first co-published their ideas of Natural Selection.

After graduating in 2005 Anthony began a career as a sculptor; other projects include commissioned busts of Ian Fleming and Carl Linnaeus. The Darwin sculpture was perhaps especially challenging, for one its full size, and of course he had no image to work from. But using the 7 and 31 year old images, as well as some of Darwin as an older man, as reference points, he has managed to produce a sculpture recognisable as Darwin.

How Was It Made?

1. the design – Anthony started by reading widely about Darwin’s life, then moved on to sketches and ‘maquettes’ which are small, rough sculptures. To get the pose right a model was hired - another Cambridge undergraduate reading Natural Sciences called Adrian Charbin from Sidney Sussex College. To make sure the detail was right lots of research was done into the sorts of clothes and books Darwin would have had.

2. constructing the armature – a steel armature was built to support the sculpture and the basic shape was formed using aluminium, steel and copper wire and expanding foam – strong enough to hold 100kg of clay!

3. Sculpting – the sculpting was done using clay, working with Anthony’s sketches, Darwin portraits and the model to help get the anatomy right. Darwin’s descendents were invited to have a look at this stage and provided a lot of great feedback.

4. Moulding – once the clay sculpture was completed a mould was made. First the clay was coated with about half an inch of silicone rubber. Next a multi-piece fibre-glass casing was made over the rubber. The rubber and fibre-glass were then peeled off carrying a perfect impression of the clay’s surface.

5. the wax – the rubber was then used to make a hollow wax replica of the sculpture, with rods of wax added to help support it and to help gases escape during the casting. This, and the next steps, were done at the Morris Singer Art Foundry.

6. the investment- the wax replica was then coated inside and out with fire-proof ceramic; these start off as fine powder, to capture the detail of the wax surface, and successive layers get thicker and thicker.

7. the casting – Next the wax was melted out of the ceramic to leave a hollow shell. The ceramic was supported in sand and molten bronze was poured in to fill the gap. Once this had cooled the ceramic was broken off to reveal the bronze.

8. the chasing – the ceramic was then cleaned off and the supports removed, and the separate parts were welded together.

9. the patination - This is one of the most exciting parts of the process of creating a bronze – the point at which it changes from being a shiny piece of metal into a sculpture. The bronze is heated up with a blow-torch and various chemicals are added which will react with the surface of the heated bronze and permanently stain it, giving it its unique 'patina'.

10. installation and unveiling - The bronze was unveiled on the bicentenary itself, in First Court, just yards from Darwin's old room. It was later moved to its permanent location in the newly created Darwin Garden in New Court – surrounded by plants that reflect those that Darwin studied and collected during his voyage around the world.

What’s The Book?

Darwin holds a book in his hand a copy of Alexander von Humboldt’s Personal Narrative, a book about a naturalist’s journey in exotic countries. Darwin read Humboldt over and over again, and it inspired him to go on his voyage. He had planned just a short trip to Tenerife, but then he got a letter inviting him to join Beagle and the rest is history. The books on the bench are William Paley’s Natural Theology (essential reading for his degree!), John Herschel’s Preliminary Discourse on Natural Philosophy, and James Stephens’ Illustrations of British Entomology in which Darwin first got his name in print in recognition of his beetle collecting. You might even be able to spot some beetles around him.

From The Sculptor

‘Seeing Darwin here, as a young undergraduate, it would have been impossible to predict the enormous impact that his ideas would someday have. But it was here, in Cambridge, that many of those interests and fascinations, that eventually led to great discoveries, were nurtured.

It has been a great honour to create this sculpture of my academic hero. And I hope that my depiction of Darwin will help people to think of him in a new way – as an energetic and adventurous young man who made the most of his ample gifts and went on to change the way we view the world.’ ~ Anthony Smith

Anthony wishes to thank David Norman, John van Wyhe, Candace Guite, Cosprop, Andrew Carragon, Simon Keynes, Philip Barlow and Alan Smith.

Written by Stephen Montgomery & Anthony Smith